featuring:

Casey Lane

- from:

-

The Parish

- recipe:

- Fried oyster poutine

405 North to 110 North. We take 6th to Spring, make a right and overshoot the parking lot. Let’s turn around. “You can’t turn right here!” says the back seat. Yeah, yeah. I hate one-way streets.

We finally park and approach what probably looks like a slice of pie from the air, surrounded by muted but colorful buildings and trees popping out of concrete. Dancing Girls? Cool sign. Where am I?

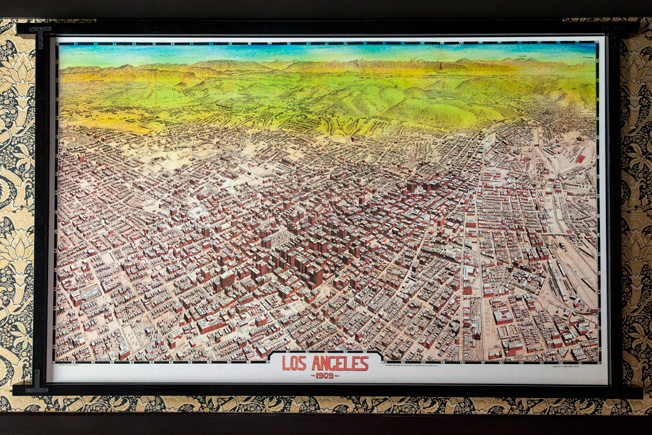

The Parish is in a unique space, triangular and tight but with lots of windows and light. A few old photos adorn the walls… vintage sepias and black & whites hanging on twisted, decorative wallpaper. You can’t miss the huge map of L.A. (for those that can’t find their way home after a few, I’m sure) or big stuffed bird or the reindeer lamp. But it’s that smell of mesquite that fills the air and the cracking sounds of an open flame that draw you to the kitchen.

Hey Casey! Nice pad…

Describe yourself. What’s your philosophy about cooking? What has always intrigued me with various things in life is essentially how things are done, where things came from. I was always the little annoying kid that asked ‘why’ constantly.

Cooking is very much the same thing. I was enamored by the process because I loved the end result as so many of us do and just sitting there looking at it, wondering, ‘Where did this come from? How did this get made? Why does someone know how to do this and I don’t know how to do it?’ which kind of leads into cooking through technique, cooking through a craft. That has everything to do with the way I design food, design menus, and constantly stay inspired as a cook and as a chef and all the other aspects of running a restaurant. It has everything to do with that search for the craft, why things were done a certain way, how things have gotten better and worse throughout time and just kind of learning to marry a bunch of different ideas and philosophies into what I end up considering my own.

What exactly is “cooking by technique?” Cooking by technique is exactly what it sounds like, learning to actually cook. It would be comparable to laying down a base for understanding how to play guitar. You need to learn the scales, you need to learn the chords, and then what you do with those is your own interpretation. If you just learn a song, it’s like learning a recipe or like learning a dish, all you know is that. You don’t understand where it came from or how it came about or how to use it to innovate in your own direction.

I think that cooking through technique is exactly that. It’s understanding as many species of fish as you can. Understanding the texture, the fat profile, the way the skin crisps, the way the skin will never crisp, how you need to handle it and then being able to evolve your own cooking by really letting the food tell you what to do with it.

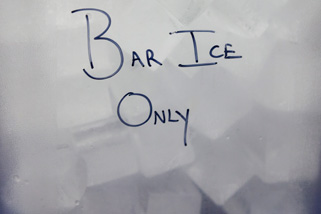

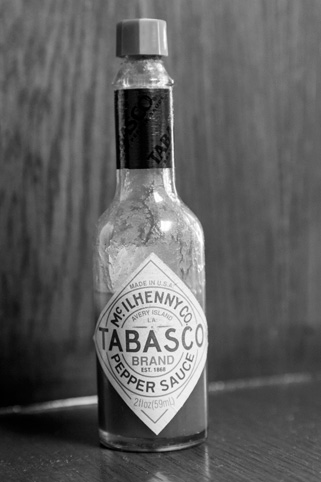

[To bar manager John Coltharp] What’s up with these ice cubes? We use big ice here and really, it’s getting back to the past more than it is the future. When bartending came into fruition in the 1800’s and when they finally had ice available around the 1860’s or 1870’s, they’d be taking big ol’ chunks of ice, hacking it up and shaking with a big cube because its easier than breaking it up into little pieces. They were getting great dilution control and amazing texture to a drink. Not over diluted, not under diluted, and that’s what we do here.

We have multiple sizes of ice for our glass. One cube in our rocks glass, one long cube in our collins glass, and we shake with one cube too. We use R.O. (reverse osmosis) water so it’s a hundred percent beautifully filtered, nearly tasteless, almost completely lacking in minerals so we get a lot of clarity out of the ice and it’s a very dense, hard style of ice. It’s a little more clear and it’s very pretty in the glass, which we love as well because the aesthetic is part of this. To us, it’s so much about function over form, but thankfully we get great form out of it as well.

[Back to Casey Lane] Where are you from, originally? Originally El Paso, Texas. I grew up in-between there with my parents and my other set of grandparents who have some large ranch properties out in New Mexico. On one of the ranches, I mean, I grew up with 30, 40 head of bison and herds of cattle and chicken and eggs and fresh produce and everything. My mom’s family, they are the ones who lived in El Paso, and who I was raised by for a good portion of my life, they’re the ones who were all born in France and ended up making food a large part of my life from a young age. I was just a kid coming home and having chocolate croissants made, you know, not Pillsbury cookies like everyone else gets. That really captured my awe of ‘How did this happen? How did you do this? Why does no one else know how to do this?’

So between the two, it’s funny because maybe being a chef was never what I was suppose to do, especially if you ask anyone in my family. They all come from different backgrounds that would be supposedly more successful [he chuckles], but at the end of it, I can definitely see where those thoughts came from and why I decided to walk the path I have.

How’d you end up in Los Angeles? I was cooking around Portland, right before I started Clarklewis, and I really lost all hope in food, thinking I might as well go work for a country club and make a good amount of money and not really push boundaries because no one out there was legitimately pushing boundaries. Everyone out there was running their mouths and not backing it up with anything behind closed doors. Then I started at Clarklewis and I saw the concept and I saw the people and I saw the food and I saw what was going on. I thought, ‘Wow you guys are going for broke. At the end of the day, you guys aren’t running a successful business, but you’re running a great restaurant.’

It really inspired me to get back into it, to try and marry those two; be a successful business and a great restaurant, which is a very, very difficult thing to do, especially in a small market like Portland.

A gentleman named Daniel Mattern, he now runs a restaurant called Cooks County, he started out through Campanile, was chef de cuisine there and AOC and Lucques, he worked with Nancy Silverton, he worked with Mark Peel, he worked with Suzanne Goin and he ended up coming up to Clarklewis to be the executive chef for a little while.

Things ended up not working out the way they wanted to, so he moved back down to LA and he was talking about opening a restaurant. I really liked working with him, I really believed in his food. It was during the second great depression or whatever, 2008 or 2009, and I thought, ‘Man I gotta get out of here. If I’m going to continue doing this I’m going to have to find a market that can support this.’ We talked about doing a restaurant together, and though that kind of fell through, I still had this ambition to come do this. So I started searching for jobs and then landed in L.A. with a Craigslist ad, the way all food endeavors start, and ended up kind of making this happen.

How did you get the name The Parish? Sifting through and throwing darts. [He laughs] It was half that, I got to be honest. We went through a lot of different names and when someone said ‘The Parish’ we all though ‘yeah, I like that.’ It’s almost too much, it’s almost one of those names where you say ‘you guys really tried, but it’s not quite there.’ We all liked the term at the end of the day because it’s a very exalted term. It’s something that feels and sounds just a little bit important and concrete without having to be so of the moment or so chic, so to speak. We really enjoyed that, we enjoyed the way that it looked and from there it just kind of ended up matching.

England was run by the church and by the parishes; and you have downtown Los Angeles with it’s various parts of the city from the historical, to the fashion district, to the diamond district. We thought of it in those terms and it just seemed to be the one that stuck in everyone’s mind because we didn’t hate it. Seriously, anything you sit with for too long you begin to hate, it’s like a marriage.

Do you consider The Parish a church? No [he laughs and shakes his head]. If you want to interpret it that way, it’s what we hope for, to be the gathering place for this district of Los Angeles, but other than that…

Which kitchen tool could you not live without? A mortar and pestle is a very simple answer… maybe a cleaver and a mallet for butchery.

We do everything by hand, so even the most difficult cuts, short of sawing bone marrow in half, we do by hand. We don’t have bandsaws, we don’t… well, very rarely we use food processors of any kind, so we do everything on a mortar and pestle and we do everything with a cleaver and a mallet. We take down steers, we take down pigs, everything with a cleaver and a mallet. They did it for a very long time that way and you just have to know the process behind it and get a little bit better than just running something through a bandsaw.

When and how did cooking capture you? I don’t know. It’s just one of those things that happens, right? It’s like when you know you’re in love with someone, it just kind of happens and you question why and you’re not sure what’s going on, but you know it’s where you are and where you’re headed.

That’s really all that I can explain of it. Maybe it started cooking with my grandfather when I was 6 and seeing him just making simple pasta and me asking, ‘How did you do that? Why do you know a lot about finance and other things, but you also know how to do this?’

I like eating, I like going out, I like drinking, I like all of it, so I think food was an easy capture on me.

How do you see the future of the culinary world? I don’t know, it’s so hard to tell. I thought it would have peaked five years ago and it seems to not have. It seems to keep pushing, keep going. It seems to be on more people’s radar. More people are going to ‘the middle of the road’ restaurants, and I mean that not in quality but price point and experience, and elevating the bar for everyone. Restaurants like Son of a Gun, Animal, The Parish, Pizzeria Mozza, places where the price point isn’t unattainable for most people, they’re putting out a quality of food and product that’s up there with the best in the industry. What you get there is expectations pushed, you get quality pushed, you get everything, you know?

So this is all affecting fine dining, right? If I can get an amazing meal for fifty dollars, you’re telling me you want a hundred and ten? That had better really blow me away. We knew that was happening, but what nobody really expected is what you’re seeing happen even at your lower end restaurants, they’re having to elevate their game in terms of where their product comes from and what they’re putting on the table, and not just in terms of a health, but in their flavor profiles and in the sourcing of their products.

the recipe:

Fried Oyster Poutine

- Fries (recipe below)

- Gribiche (recipe below)

- Gravy (recipe below)

- Oysters (recipe below)

- Fry the fries in 350 degree oil for about 5 in. or until crisp and golden.

- Spoon about 1/4 c. of gribiche into the bottom of your serving bowl.

- Heat about 1/2 c. of the gravy and toss the fries in the pan. Toss and coat the fries well, then place in your serving vessel over the gribiche.

- Top with 3 fried oysters and a squeeze of lemon.

Fries

- 4 russet potatoes

- Cut potatoes into 1/2 in by 1/2 in fries.

- Blanch in peanut oil at 225 for about 25 min.

- Strain fries and pat dry.

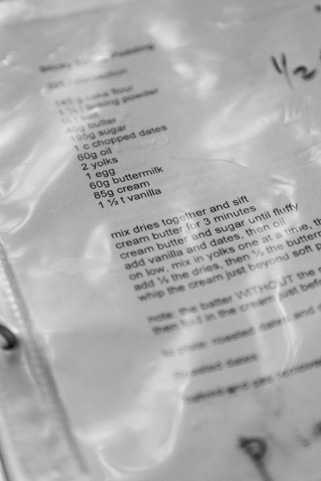

Gribiche

- 1/2 c. aioli

- 1 serrano pepper

- 1 shallot

- 1 hard boiled egg

- 1 tbsp. minced chives

- 1 tsp. piment d’espelette

- Salt to taste

- Brunoise the serrano pepper

- Brunoise the shallot

- Mince the hard boiled egg

- Mix the ingredients into the aioli and season with salt to taste.

- Allow aioli to "bloom" for about 30 min. before use.

Gravy

- 1 c. pork stock

- 1/4 c. roux

- 15 pieces bacon lardon

- 1 small leek (julienned)

- 1 tbsp. mortared garlic

- Salt to taste

- Saute leeks and garlic until translucent

- Add lardons and crisp

- Add roux to the pan and stir together

- Add pork stock and bring to a simmer

- Simmer for about 20 min. on low heat and season to taste with salt

Oysters

- 12 large shucked frying oysters

- 2 c. buttermilk

- 2 c. flour

- Dip oysters into buttermilk

- Dredge oysters in flour

- Fry in 350° oil for about 7 min. until golden brown and crisp